This year’s Curatorial Incubator has drawn to an end. This year we invited eight incubatees to each make a program that responds to the theme of “Living In Hope.” In keeping with the restrictions of COVID-19, we took the entire program online, unrolling one title per week, with a Zoom conversation at the end of each program featuring the curator and the artists.

The eighth – and final – program in this year’s Curatorial Incubator opened Friday, March 5, 2021, with a Zoom Live introduction by emerging curator Shalon Webber-Heffernan, followed by the first title in her program, Acoustic Ocean, by Ursula Biemann.

On Friday, March 26, 2021, Shalon Webber-Heffernan was in conversation with artists Ursula Biemann, Shelley Niro, prOphecy sun, and Sharon Isaac.

Image credit: Traces of Motherhood, by prOphecy sun (2016)

PROGRAM #8 Curated by Shalon Webber-Heffernan

love as rupturous as I know it to be

Becoming a new mom in a global pandemic has been an experience that’s shaped me in ways I cannot yet know, but know are extraordinary. My heart’s new colossal capacity has prompted me to consider anew a genuine ethics of care that reaches beyond the performative care I see unfolding in a variety of cultural and political settings today. love as rupturous as I know it to be ponders caring otherwise, prioritizing action while envisioning a radical unbounded love. Intuitively, instinctively, and uninterested in aesthetic distance, I selected works that spoke to me viscerally. I was guided by a desire to explore relationships that exceed those that are strictly between humans to include those that exist between plants, animals, and things, and merge into minerals, energy, land, stars and waters. Curator Tarah Hogue once described how the work of Michif artist Christi Belcourt “nurture[s] relations through kinship networks that are place-based, inter-species and otherworldly, and in turn demonstrates, through beauty, strength and wonder, that other (to colonial capitalist) ways of being in relation to one another and to the earth are both possible and desperately urgent.”(1) These other ways of being have inspired me in thinking through what a hopeful future might feel like.

The title of this series is an excerpt from an essay (2) by Karyn Recollet that imagines cosmic kinship and imagines the potent magic of dark matter—the vibrant power of imagining elsewise. These videos symbolize an ethos of generosity—a central tenant for intimate practices of care in a world wildly in need of renewal. They simultaneously index the grave responsibility necessary if ongoing flourishing of life is to be sustained. Understanding that all our complex and fragile interactions are inextricably linked requires acknowledging our dependency, collective need, grief, and reciprocity as basic elements of being. Transformation calls for a rebirth of the world as we know it and demands we are brave enough to face the troubling vulnerability and shattering affective burden of living in hope.

___________________________________________________

(1) Hogue, Tarah. “Walking Softly with Christi Belcourt.” Canadian Art. June 21, 2017.

(2) Recollet, Karyn. “Kinstillatory Gathering.” c mag, Issue 136.

Shalon T. Webber-Heffernan is a curator and doctoral candidate in Performance Studies at York University. Her work broadly examines feminist performance projects that respond to issues surrounding borderlands, space, and disappearance throughout the Americas. She was Curator in Residence at the Curatorial Lab @ Sensorium Centre for Digital Arts and Technology (2019-20) and recently worked with Toronto’s 7a*11d and grunt gallery.

_________________________________________________________________________

love as rupturous as I know it to be

Ursula Biemann, Acoustic Ocean, 2018, 18:00

I close my eyes and imagine the calmest cold waters—a profound solitude.

The midnight blue sounds and vast environment of Ursula Biemann’s Acoustic Ocean evoke meditative, magical thinking in deep time. Sonic frequencies and fin whale vocalizations swell in my heart. The absence of a sea butterfly’s heartbeat foretells of things to come. A whale’s memory chamber holds secrets of an ancient future. A dolphin’s ghost is free and swirling away from all entanglement.

Biemann’s oceanic video installation probes the acoustic dimensions of marine life in the North Atlantic. Located on the Lofoten Islands in Northern Norway, the video centers on the performance of a Sami marine-biologist-diver who is using a model of a submersible equipped with hydrophones and recording devices. In this science-fictional quest, the aquanaut’s task is to sense the submarine space for sonic and bioluminescent forms of expression and feeling—interconnected relations between marine, human, scientific, energetic, and digital worlds become enmeshed.

Shelley Niro, Tree, 2006, 05:00

In a dream I had, a pregnant woman was a tree and in her grasp was every kind of plant. She was the holder of wisdom, pain, and all the love in the world.

Shelley Niro’s Tree is a tender film that acknowledges the import of spiritual connectivity while illuminating the pernicious nature of slow violence. The atmosphere of Niro’s film is austere, barren. A woman personifying earth bears witness to the murderous fallout of capitalism, ecological destruction, and spiritual collapse. In her 2013 book Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall Kimmerer writes that “grieving is a sign of spiritual health. But it is not enough to weep for our lost landscapes; we have to put our hands in the earth to make ourselves whole again.”

The woman listens with a broken heart to the visions of earth. Her body transmutes, returning to eternity. We sense that she may return once healing and the balance between humans, land and water have been restored.

prOphecy sun, Traces of Motherhood, 2016, 02:20

I’ve been reflecting on the ordinary, day to day elements of motherhood, like eating cold curry at 10:00 a.m. on zero sleep while my baby screams—trying to approach these less than fabulous moments with openness, mindful attention, and awe. The entirety of life in a single moment.

prOphecy sun merges minutiae with magnificence in her video art practice. sun uses smartphone technology to capture task-like movements, and improvisational gestures as she walks with an atmospheric weather balloon and a small child through vast, open land.

Traces of Motherhood is part of a multi-channel video and sound installation that considers how the body responds to the agency of things in the world. The work emphasizes temporality and the technological unconscious, and our ability to sense and perceive different forms of media that are visual, aural and tactile. Traces of Motherhood contemplates non-human sites as performing entities and the environment as active collaborator.

Sharon Isaac, Dancing with Naango, 2018, 03:17

My daughter stares with wonder at the leaves flitting in the wind and reaches out for their succulent green flesh.

Sharon Isaac’s film Dancing with Naango makes me think about matrilineal lineages and of place. I watch it and wonder about dance as embodied knowledge transfer, ancestral presence, trauma, and the healing properties of joy. Isaac’s film traces her daughter’s journey as a Jingle Dress dancer, and is a gentle dedication to her Great Grandmother, Naango (Star).

The film is an oral and visual retelling of the reasons her daughter dances and the deep importance of maintaining her Ojibwa traditions. The distinctive rattle and clink of the metal cones and the hopeful prayers invoked through the dance spark a tingling sensation. The gestures in this work overflow with jubilation and are sensitive to that which cannot be encapsulated through words. There is a quality of light that shines with undiminished luster.

PROGRAM #7 Curated by Camila Salcedo

Performative Faiths (Spanish-language text below)

Growing up in Venezuela, my grandparents had altars in dedicated rooms in their homes, and they lit candles throughout the day for the “ánimas benditas,” souls in limbo that had not yet transcended into heaven. Popular traditions embracing the dead, like this one, are widespread and commonplace sources of hope in Venezuela, primarily for those living in the most impoverished and violent communities, whether in city barrios or in rural communities, where untimely death occurs often and unjustly. In cemeteries in the most crime-ridden areas of Caracas, people pray to the santos malandros (“holy thugs”), a sect of outlaw saints with a large cult following, such as Ismael Sánchez, known for performing crimes of generosity not unlike Robin Hood. These saints derive from the spiritist faith, part of Venezuela’s María Lionza religion, which reveres a mestiza goddess of the same name and borrows from colonial Catholicism, as well as Afro-Caribbean and Indigenous faiths. “María Lionzeros,” those who practice the religion, embrace death through many rituals, including ones by which religious leaders invoke and embody the dead.

Popular beliefs and santos that keep death at the forefront, similar to the ones in Venezuela, are embedded in the social fabric across Latin America. The artists’ works selected for this series reinterpret the rituals of these faith-based traditions. In the process of making consistent, Guillermina Buzio examines the tradition of altars dedicated to those who have suffered tragic deaths throughout Argentina. Nela Ochoa fictionalizes her own experience of faith-based rituals while growing up in Venezuela by subverting Catholic gestures in que en pez descanse, or “may [they] rest in fish,” a pun on the popular myth that if one bathes in the ocean on Holy Friday one will turn into a fish. In Exercises in Faith: Embrace, Julieta Maria questions sacrificial offerings by literally taking the life of a fish by intimately embracing it with her hands. Through their performative actions, the three artists explore popular traditions that give people hope in the face of death in Latin America.

Camila Salcedo is an interdisciplinary artist, independent curator, community facilitator and arts educator based in Toronto. She is interested in unlearning, questioning, and dismantling systems and institutions that were created to define us such as nations, identity, politics, and migration. She has a BFA from NSCAD University from 2018.

_______________________________________________________________________

Performative Faiths

Guillermina Buzio, the process of making consistent, 2009, 05:55

the process of making consistent is a video performance in which the artist sits naked in a set that recreates a “Gauchito Gil” altar located near the site of her mother’s accidental death during Argentina’s dictatorship. The artist describes this performance as “healing and painful,” evoking both past and present traumas. In it, she remains motionless as her friends and strangers adorn her with photographs, trinkets, and prayers, emulating altars devoted to those who have died tragically. The work also weaves photographs of the “Gauchito Gil” altars, a gaucho (cowboy) outlaw figure widely revered in Argentina as a saint, and videos of the Crogmañon Altar, an altar for the 194 people who tragically died in a nightclub fire in Buenos Aires. At the bottom of the screen a text scrolls of invented prayers, as well as written wishes, through which the artist commemorates her loved ones.

Nela Ochoa’s Video Cruz 1492, Video sculpture for Que en pez descanse, 1986, 16:35

que en pez descanse is a surreal video work modeled after the artist’s childhood. All of the characters have cult-tendencies, except for the main character who is distrustful and apprehensive of society’s rules. The characters perform odd choreographic gestures that are slightly “off” from the traditional gestures of the Catholic faith. For example, instead of “crossing” themselves with their right hand, they do it with both hands; instead of kissing the small cross made by their index and thumb, they put their hand into their mouths; instead of taking communion wafers, they ingest a whole live fish. The title is a pun using the word “pez” meaning fish, instead of “paz,” meaning peace, and directly translates as “may [they] rest in fish;” it is also a reference to the popular belief that if a person bathes on Good Friday, the day commemorating Christ’s crucifixion, they will become a fish.

Julieta Maria, Exercises in Faith: Embrace, 2011, 06:00

Exercises in Faith: Embrace is a video performance in which the artist sacrifices a live fish that was destined for human consumption and decontextualizes the purpose of its life by killing it for the sake of art. In this “exercise in faith,” she exercises her control and power over the fish by holding it in her hands and hugging it carefully against her chest until it slowly passes away. In the middle of the video, the action subtly starts to replay backwards, so that if looped, the fish will remain in perpetual agony. This can be an incredibly difficult performance to watch, as one observes the artist inflict death upon a live animal during what is usually an act of care – a hug or “embrace.” The artist explores how “faith” and “trust in god” are used as coping mechanisms for living, even though death is our eventual destiny.

PROGRAM #7 Curated by Camila Salcedo

Santas del Pescado

Mientras yo crecía en Venezuela, mis abuelos tenían cuartos dedicados a altares en sus casas, donde prendían velas a las ánimas benditas (del purgatorio), almas en el limbo que aún no habían trascendido al cielo. Tradiciones que acogen a la muerte son fuentes comunes y extensas de esperanza en Venezuela, principalmente para aquellos que viven en las zonas más pobres y violentas, como barrios o comunidades rurales, donde asesinatos inesperados suceden con frecuencia. En los cementerios de Caracas ubicados en las zonas más violentas, las personas le rezan a los santos malandros, una secta de santos criminales con grandes seguimiento de culto. Un ejemplo de estos santos es Ismael Sánchez, quien es conocido por haber cometido crímenes generosos como el personaje de Robin Hood. Estos santos provienen de la fe espiritista, parte de la religión María Lionza en Venezuela, la cual venera a una diosa mestiza del mismo nombre, tomando tradiciones y creencias del Catolicismo colonial y religiones Afro-Caribeñas e Indígenas. Los María Lionzeros involucran la muerte a través de rituales en los que evocan y encarnan los muertos.

Creencias populares que acogen a la muerte y a los santos malandros, similares a los de Venezuela, están inmersos en el tejido social en Latinoamérica. Los trabajos elegidos para esta serie reinterpretan los rituales de estas tradiciones basadas en la fe. En the process of making consistent (el proceso de hacer consistente), Guillermina Buzio examina la tradición de los altares dedicados a aquellos que han sufrido muertes trágicas alrededor de Argentina. Nela Ochoa lleva a la ficción los rituales de fe que experimentó durante su niñez en Venezuela, al subvertir gestos Católicos en que en pez descanse, obra basada en el mito de que uno se convertirá en un pez si se baña en el mar un Viernes Santo. En Exercises in Faith: Embrace (Ejercicios en Fé: Abrazo), Julieta Maria cuestiona ofrendas sacrificiales al literalmente darle muerte a un pez mientras lo abraza íntimamente en sus manos. A través de sus acciones performáticas, las tres artistas exploran tradiciones populares Latinoamericanas que dan esperanza ante la muerte.

Santas del Pescado

Guillermina Buzio, the process of making consistent, 2009, 05:55

the process of making consistent (el proceso de hacer consistente) es un video-performance en el que la artista está sentada desnuda dentro de un escenario construido que recrea un altar a Gauchito Gil, el cual estaba situado cerca del lugar dónde su madre falleció accidentalmente durante la dictadura argentina. La artista describe este performance como “curativo y doloroso,” ya que evocó traumas de su pasado y su presente. En el video se mantiene inmóvil mientras que sus amigos y extraños la adornan con fotos, objetos y oraciones, emulando altares dedicados a quienes han muerto trágicamente. El video también entrelaza fotos de altares de Gauchito Gil, un gaucho y figura criminal conocida y venerada en Argentina, y videos del Altar de Cromañón, dedicado a las 194 personas que murieron trágicamente en el incendio del “boliche” en Buenos Aires en el 2004. En la parte de abajo de la pantalla hay un texto móvil con oraciones inventadas y deseos, a través de los cuales la artista conmemora a quienes ama.

Nela Ochoa, que en pez descanse, 1986, 16:35

que en pez descanse es un video surreal basado en la niñez de la artista. Todos los personajes tienen tendencias de culto, menos el personaje principal, quien desconfía de las reglas estrictas de la sociedad. Los personajes actúan gestos coreográficos de la fe Católica incorrectamente, como por ejemplo, en vez de hacer la cruz con la mano derecha, lo hacen con ambas manos; en vez de besar la cruz hecha por su pulgar y dedo índice, meten la mano entera dentro de su boca; en vez de tomar la comunión, ingieren un pez vivo. El título es una referencia a la creencia de que si uno se baña un Viernes Santo, el día que conmemora la crucifixión de Jesús, uno se convertirá en pez.

Julieta Maria, Exercises in Faith: Embrace, 2011, 06:00

Exercises in Faith: Embrace (Ejercicios en Fé: Abrazo), es un videoperformance en el que la artista sacrifica la vida de un pez que estaba destinado a morir para ser consumido, y descontextualiza el propósito de su vida al matarlo para hacer arte. En este “ejercicio en fé”, ejerce su control y su poder sobre el pez, al acogerlo en sus manos y abrazarlo en contra de su pecho hasta que lentamente muere y se convierte en pescado. A la mitad del video, la acción empieza a repetirse al revés, de manera de que si es looped, el pez se mantendría en agonía perpetua. El performance puede ser muy difícil de ver, ya que uno observa a la artista matar a un pez durante lo que es normalmente un acto de cariño, un abrazo. La artista explora cómo la “fe” y la “confianza en dios” son utilizados como mecanismos de supervivencia, aunque la muerte es nuestro destino eventual.

PROGRAM # 6 Curated by Robin Alex MacDonald

“It could be a good day. It needs to be treated carefully.”

The sixth program of this year’s Curatorial Incubator started Friday, January 15, 2021, with a live introduction by emerging curator Robin Alex McDonald, followed by the first title in their program, Hope, by Dana Claxton.

On Friday, February 5, 2021, Robin Alex McDonald was in conversation with artists Dana Claxton, Gary Kibbins, Jorge Lozano and Rokhshad Nourdeh at 7pm EST.

In the 1998 novel The Hours, Michael Cunningham’s fictionalized character of Virginia Woolf awakens one morning into a liminal state, still half-present in the lush green park she was dreaming of moments ago. As she moves from the park into her bed and then into the bathroom, she carries the feeling of the park—its “banks of lilies and peonies, its graveled paths bordered by cream-colored roses”—with her. Crucially, Virginia avoids looking into the bathroom mirror above the basin, where she knows she will be met with an image that holds the potential to startle and disturb her. Neither does she enter the kitchen, where her servant Nelly awaits. Honouring the fragility of her memory of the park, of her concentration and will to work, of the day itself, she heads straight to her desk where she can buoy the feeling of the park and her own spirits through writing. She declares: “It could be a good day. It needs to be treated carefully.”

Virginia understands that her cautious optimism must be handled with care, like an object prone to shattering. Adopting this same delicate and protective approach, “It could be a good day. It needs to be treated carefully” showcases works in the Vtape collection that present hope as “an inherently risky, fragile project.”1 Each of the four works present narratives of hope anchored in a fragile object – a bowl, a doorway, a butterfly, and a line, respectively. Highlighting precariousness as a fundamental feature of hope’s structures, the underlying question of the program asks: how might we hold out for hope without falling victim to forms of “cruel optimism”?2 Poetic and anxiety-provoking, desirous yet wary, these four works invite us for a walk along the tenuous line between hope and dejection.

Robin Alex McDonald is an academic, independent curator, and arts writer. They currently work as a part-time faculty member in the Fine and Visual Arts department at Nipissing University in North Bay, an instructor in the Visual and Critical Studies program at OCAD University in Tkaronto/Toronto, and a PhD Candidate in the Cultural Studies Program at Queen’s University in Katarokwi/Kingston, Ontario.

“It could be a good day. It needs to be treated carefully.”

Curated by Robin Alex McDonald

Dana Claxton, Hope, 2007, 09:51

In Dana Claxton’s Hope, a pair of hands carefully repairs a broken bowl, each piece fitting neatly back into its original position. Just when the bowl appears whole again, the hands begin to disassemble it and the process repeats. Though Claxton is Lakota and resides on Coast Salish territory, I cannot help but draw a connection between the bowl in Claxton’s video and the Dish with One Spoon territory: the land on which I spent the first twenty years of my life and on which Vtape’s offices are located. That “we all eat from the same dish” with a single spoon serves as a reminder of our shared responsibility to care for the land—but like the bowl in Claxton’s video, this sense of mutual cooperation is brittle. While every destruction of Claxton’s bowl is swift, each repair becomes increasingly more difficult.

Gary Kibbins, Doorway, 2017, 07:30

Positing the titular space as both an existential and literal interstice, Gary Kibbins depicts the doorway as a bridge between two realities: what is, and what might be. Doorway presents a dramatic narration of the artist’s encounter with a particular door, one equipped with a well-worn Nina Olivari lockwood 13-60 handle and laden with promise and potential: “However unexceptional in my life, I could still visualize a different life. A better life. A life full of success, love and adventure on the other side of that door,” he explains. For Kibbins, the arc drawn by the door’s pathway as it swings open creates a kind of hammock, a space where hopes and possibilities can be temporarily suspended, cherished, and cradled. Although this hopeful space is easily (fore)closed, its mere existence serves as a reminder to viewers of our own abilities to wilfully transform quotidian sites into experiences of expectation, anticipation, delusion, and disappointment.

Jorge Lozano, The Butterfly Effect, 2018, 06:44

For a young Jorge Lozano growing up in Columbia, the act of spotting a Blue Morpho butterfly served as a token of good luck. In The Butterfly Effect, Lozano’s camera scans frantically, possibly hoping to catch a glimpse of another Blue Morpho, but the video’s text informs us not to get our hopes up: “good luck and happiness are rapidly disappearing.” Like Cunningham’s fictitious Virginia Woolf, Lozano’s reference to Daoist philospher Zhuang Zhou’s “butterfly dream” suggests that the line that divides dreams from reality (just like the line that divides self from other, or presence from absence) might be more nebulous than we assume.

Rokhshad Nourdeh, Raid-Line, 2006, 02:07

While all four works in “It could be a good day. It needs to be treated carefully.” explore the figurative line between hope and dejection, Rokhshad Nourdeh makes this line literal by dragging red chalk across the floor below her. In Raid-Line, a pair of bare feet struggle to walk the red streak like a tight-rope, bleeding and blurring the chalk as they endeavour to grip the ground. Anxious and uncertain, the feet draw figure-eights in the air as if divining where, exactly, to land. Eventually, they untether themselves from the chalk line, gliding and pivoting across and around it and exposing the false dichotomy it creates.

PROGRAM #5 Curated by Karina Griffith

Endarkened Perspectives

What if darkness were not the opposite of light, but instead could do and be everything light can do and be, and much more? This programme looks at moving images through Cynthia Dillard’s concept of “endarkenment” (a response to Enlightenment that imagines a new world order centring Black feminist thought). These short films and videos flip the switch to turn darkness and mystery into something that can be illuminating, broadening and blazing.

The proposed curatorial investigation asks: “How can moving image reflect an endarkened way of experiencing the world, and despite that experience, live in hope?” These “epistemologies” or ways of knowing and learning shift what is considered “normal” to make room for diverse intersections of gender, indigeneity, class and ability. To apply this concept to moving image, I engaged with Dillard’s methodology of “research as responsibly” to search the Vtape archives for examples of what she calls “life notes”: the words and writings and revelations of women when they are free to speak from the heart rooted in storytelling practices: the song, the dance, the poem, the lullaby. It meant looking through the titles to build on femme expressions of life to create a new canon distant from white male ableist supremacy.

The program seeks to find filmic texts that reflect endarkening not only in content but in form, through reversals and bold contrasts in their treatment of sound and cinematography, light and dark.

Karina Griffith is a visual art, film scholar and curator based in Berlin and Toronto. Her moving image, textile and paper works explore the themes of fear and fantasy, often focusing on how they relate to belonging. Griffith writes for Texte Zur Kunst, Canadian Art, Berlin Art Link, Missy Magazine, Shadow & Act, among others. She is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Toronto’s Cinema Studies Institute. She holds a lecturer position at the Institute for Art in Context at the Berlin University of the Arts (UdK).

On Friday, January 8, 2021, Karina Griffith will be in conversation with artists Dana Inkster, Thirza Cuthand, Penny McCann, and Abdi Osman at 7pm ET on Zoom. Check the Vtape website for a link to this conversation.

Endarkened Perspectives

Dana Inkster, From Billie…To Me… And Back Again, 2002, 4:20

A radio dedication evokes an ephemeral encounter in this short experimental film by Dana Inkster. Exaggerated performances of high and low voices play with gender expectations of Black love before the soundtrack gives way to Billie Holiday’s You’re My Thrill (1949). Reverse photography of a pair of hands switches the perspective, a denial of film convention that turns light and dark. Billowing smoke in the tight frame obscures the image and the identity of the lovers, as does the shadow play of two heads joining in a kiss. The film’s cyclical form and use of repetition fit the narrative like a needle in a record groove, a visual and sonic expression of open, endarkened love.

Thirza Cuthand, Sight, 2012, 3:33

The unseen of endarkened perspectives is given literal form in Thirza Cuthand’s work Sight. The film tells the true story of a relative of Cuthand, who lost his vision and her bout with temporary blindness to question Western ideas about sanity and the treatment of mental illness. Cuthand manipulates Super 8 footage to obscure images of exteriors and speaks in the irresistible deadpan tone typical for her work. Sight is about seeing as much as it is about how we are seen – by family, by institutions and by the Enlightenment ideologies that create structural inequalities in Canada.

Penny McCann, Marshlands, 2000, 6:07

Endarkenment opposes Enlightenment, where Dillard positions “white feminism.” However, similar to intersectionality, I feel through endarkenment as space from which many orientations can question established. Penny McCann’s films challenge western expectations of women through narratives of femme magic in rural Canada. Her experiments in super 8, 16mm and video evoke the unseen energies of endarkened possibilities. The short, experimental film Marshlands set in and around Sackville, New Brunswick, a town in Eastern Canada, opens with fortune-telling. This claiming of the unknown situates the film in a defiant witchery. Visually, McCann expresses this with overexposed images, changes in lighting and contrast. The alarming sound of barrelling trains and blurred images of their approach affectively stimulate alarm. McCann’s sparse on-screen texts describe the memory-soaked air, and her defiant attempt to escape it: “The marsh is a place of unsettling dreams, of tides, and impossible structures. I wait for the train.”

Karina Griffith, Repair, 2017, 5:47

I looked at my work through the gaze of endarkened perspectives and found them in Repair, a film about my grandfather’s house in Georgetown and the rainforest in Guyana. It is estimated that more Guyanese live outside the country than in it — my diasporic longing for home and my great aunt’s knowledge about the healing properties of plants come together in these filmic field notes. Similar to the hidden stories of McCann’s Marshlands, the mystery of forgotten oral histories hang in the air between the rains in Repair. I was struck by a similar approach in another work in the Vtape archive, Maigre Dog (part of Yaniya Lee’s programme fractured horizon – a view from the body). Donna James explores the riddles of Jamaican patois with elders – storytelling with cryptic still life video treatments. Creole is the equivalent of a secret language, an endarkened and empowered tactic for living hope in colonized spaces.

Abdi Osman, Labeeb, 2012, 4:23

Endarkened perspectives encounter performance in Labeeb. Sumaya, a mesmerizing Somali trans-woman, plays with expectations and with the spectator, taunting the gaze on her performance of a Somali ritual. The narrative is veiled and opaque, like the translucent shawl between Sumaya’s fingers. Where other endarkened cinemas in the programme skirted film convention with photo reversal, Osman balks at expectation with cuts that jump the axis and a dissected frame of diptychs and creative triptychs created with a mirror. Moments of silence further assert the right to be opaque.

This year’s Curatorial Incubator, taking place in these (as we say) unprecedented times, is a bit of a different beast. This year we invited eight incubatees to each make a program that responds to the theme of Living In Hope. In keeping with the restrictions of COVID-19, we are taking the entire program on-line, unrolling one title per week with an on-line Zoom conversation at the end of each program featuring the curator and the artists.

PROGRAM #4 Curated by Ivana Dizdar

A truth, if it is a truth.

The fourth edition of this year’s Curatorial Incubator starts Friday, November 13, 2020, with an Instagram Live introduction by emerging curator Ivana Dizdar at 7pm ET followed by the first title in her program, The Violence of a Civilization Without Secrets by Zack Khalil, Adam Shingwak Khalil and Jackson Polys.

On Friday, December 4, 2020, Ivana Dizdar will be in conversation with artists Zack Khalil, Adam Shingwak Khalil and Jackson Polys, Akram Zaatari, Sharif Waked, Niklas Vollmer and Laura Kissel at 7pm ET on Zoom. Check the Vtape website for a link to this conversation.

Image credit: Unfettering the Falcons, Niklas Sven Vollmer and Laura Kissel (2007)

My first migration occurred in utero. Having fled their native Yugoslavia during the Civil War, my parents temporarily settled in South Africa. In their first photograph in Cape Town, they are standing on a headland at the southernmost point of the continent, my mother visibly pregnant. Before them is a large wooden signboard inscribed with the words “Cape of Good Hope.” It is an undeniably romantic epithet and, surely, for my parents, there is hope to be found. But just how good, how ubiquitous, could it be? With the end of apartheid approaching yet still a year away, what the Cape could represent was only a discriminative, fraught, and elusive sense of hope.

I see the theme of this year’s Curatorial Incubator, “Living in Hope,” as a complex provocation, and hope itself as something invariably complicated. My pursuit to uncover buried treasures of videography in Vtape’s archive drew me to works that made me reconsider the process of uncovering as something equally complicated: something that can be the source of illumination but also of vulnerability, of risk, of harm and pain and death. Against the axiom that uncovering always or necessarily leads to truth and justice, the videos in this selection call for a recognition of its multivalence.

Ivana Dizdar is a scholar, curator, and artist. She works on the intersection of art, politics, and law, with particular interest in decolonial gestures and acts of epistemic disobedience. Her writing recently appeared in MIT’s art and architecture journal Thresholds and in Vistas: Critical Approaches to Modern and Contemporary Latin American Art.

A truth, if it is a truth.

New Red Order (Zack Khalil, Adam Shingwak Khalil and Jackson Polys), The Violence of a Civilization Without Secrets, 2017, 10:00

Science, mythology, ideology, pathology: strangers, acquaintances, friends, or brothers?

It is 1996 in Kennewick, Washington. The excavation of the “Kennewick Man” provokes a contentious debate: what is his lineage and who was here first? Erroneous and misinterpreted craniological studies incite alternative claims to Indigeneity as well as attempts to reframe, deny, and erase a colonial past.

New Red Order’s documentary-cum-manifesto, The Violence of a Civilization without Secrets (2017), traces a legal, ethical, and ontological conflict that arises when a community’s right to bury its dead is challenged by calls for anthropological research.

Discovery, evidence, authentication, testimony, and their media coverage are, in this tale of subjectivity, not marked by a pursuit of truth.

In their uses, misuses, and abuses, excavation and burial are kin.

Akram Zaatari, Time Capsule Kassel, 2012, 07:24

Iron, concrete, earth.

Iron, concrete, earth.

I grew up with an understanding that to save something can mean to bury it. Roughly translated, the root of my grandmother’s maiden name, Kaljević, is “mud.” To protect them from being kidnapped during invasions by the Ottoman militia, my ancestors, I am told, were periodically compelled to bury their children beneath layers of mud.

Artifacts and photographs are a lot like children: precious, delicate, and in need of protection. In Time Capsule Kassel (2012), Akram Zaatari re-imagines the National Museum of Beirut’s effort to conserve its collection of objects by keeping them sealed within concrete blocks for the entirety of the civil war in Lebanon. Zaatari’s work offers an extension of this model, one that entails concealment as well as burial.

Crypts, tombs, and mausoleums signify death, and yet, here, they enable the preservation of cultural life, a treasure covered in favor of its eventual recovery.

Sharif Waked, Chic Point, 2003, 07:15

“Fashion for Israeli checkpoints,” the artist calls it.

To characterize Sharif Waked’s work as a dark comedy feels wrong, and yet it is both unquestionably dark and irrefutably within the margins of humor—no—satire—no—absurdity.

It begins with a runway, with male models and their chiseled abs. High-cropped shirts, a collar misplaced above the naval, a horizontal zipper across the stomach, a gaping hole revealing chest hair and nipple. To be sure, the haute couture in Chic Point (2003) is designed to accentuate the midriff.

Suddenly, documentary photographs reveal Palestinian men forced by Israeli soldiers to prove they are not carrying explosives by lifting their clothing and exposing their abdomen: an invasive and humiliating surveillance practice, an overture to fatal endings. Why not, Waked suggests, make this biopolitical choreography more efficient, more effortless, through innovations in fashion?

After all, violence, here, has long been in vogue.

Niklas Sven Vollmer and Laura Kissel, Unfettering the Falcons, 2007, 07:20

What’s in a name? Would that which we call a falcon by any other name fly as high?

A gender-reveal party—for a bird and a football team—takes center stage in Niklas Sven Vollmer and Laura Kissel’s Unfettering the Falcons (2007). This is not the kind of nature documentary one is used to seeing on Discovery.

Identical twins Lauretta and LaVergne, both experts on birds of prey, want to set the record straight: the falcon is, by definition, a female. The only true Atlanta Falcons, they add, are the team’s cheerleaders.

Wishful football fans insist the falcon’s athletic namesake would do well to rebrand itself as her male counterpart, as the Atlanta Tercels. Unbeknownst to the fans, the tercel is smaller and—quite literally—the weaker sex.

Replete with the twins’ idiosyncratic observations, the video evokes the tension between language and gender, for the latter is unfixed and resistant to definition, sometimes slipping through the cracks of our syntax.

New Red Order (NRO) is a public secret society facilitated by core contributors Adam Khalil, Zack Khalil, and Jackson Polys. Working with an interdisciplinary network of informants, the NRO co-produces video, performance, and installation works that confront settler colonial tendencies and obstacles to Indigenous growth and agency.

Akram Zaatari has been exploring issues pertinent to postwar Lebanon. Co-founder of the Arab Image Foundation (Beirut), Zaatari based his work on collecting, studying, and archiving the photographic history of the Middle East notably studying the work of Lebanese photographer Hashem el Madani (1928-), as a register of social relationships and of photographic practices.

Sharif Waked was born in Nazareth to a Palestinian refugee family from the village of Mjedil. He lives and works in Haifa/Nazareth. Through ironic reflections on power and politics, Waked overturns established aesthetic formations and ponders the absurd realities of political conflict.

Niklas Vollmer is an interdisciplinary artist, who teaches film production at Georgia State University. Vollmer’s experimental documentary work has screened in the US, Canada, Europe, Africa, South America and Asia, and at AFI, Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art, California Museum of Photography, and the Directors Guild of Los Angeles.

Laura Kissel is Professor of Media Arts in the School of Visual Art and Design at the University of South Carolina and an Emmy-nominated documentary filmmaker. She has received grants from the Fledgling Fund, South Carolina Humanities Council, and was a Fulbright Fellow in 2009.

PROGRAM #3 Curated by Sanjit Dhillon

Slow Unfurling

I began the process of selecting these films as our established modes of being were brought to a halt. The routines and rituals that we regularly engaged in without any thought transformed into absences overnight. A rupture formed in our accelerated culture of individualism and competition.

It is this rupture, however, that has impelled a collective probing of many of the values entrenched in capitalist life. This program forms a deeper investigation into how these values are upheld and consequently shaped our ability to imagine future outside of capitalism. The films presented in Slow Unfurling arrest these socio-political constructs with stillness, contemplation and reflection.

Mark Fisher says that capitalism has not only become the only viable political and economic system, it has become impossible to imagine a coherent alternative. In the contemporary moment, the only option is to envision and work towards an alternative. Through ongoing reflection, as exemplified by these films, the potential for imagining new ways of living beyond reformist principles can be proposed. To do so is to live in hope.

Sanjit Dhillon is a multidisciplinary artist, curator and cultural worker based in Tkaranto/Toronto, Canada. Her practice interrogates constructions of memory, embodied subjectivity, precarity, and the limits of visual culture in creating and disseminating identity. She has curated for Xpace Cultural Centre, DUTY FREE zine and participated in residencies at Whippersnapper Gallery and Roundtable Residency.

On Friday, November 6, 2020, Lisa Steele will speak with artists Erika DeFreitas, Johan Grimonprez, and Saskia Holmkvist at 7pm ET on a recorded conversation. Look for this on the Vtape website, followed by the final title in her program

Slow Unfurling

Erika DeFreitas, forgive me for speaking in my own tongue – 4 mins and 12 secs before entering melancholy, 2016, 04:12

forgive me for speaking in my own tongue – 4 mins and 12 secs before entering melancholy depicts the artist, Erika Defreitas, in a state of meditative breathing. Focusing on each inhale and exhale, the act of breathing surpasses biological necessity to become an act of asserting presence. In the larger context where the right to life continues to be contested, the ability to breathe easily–without anxiety or urgency–is not guaranteed for all. Her intentionality towards presence becomes an act of resistance.

Raymond Tallis on tickling, Johan Grimonprez, 2017, 08:00

Neoliberal individualism requires a collective consciousness to uphold and sustain it. Raymond Tallis on Tickling proposes that there are no individuals, as consciousness is fundamentally relational. Tallis remarks: “We are ourselves only through being in dialogue with others.” Tallis challenges the notion that humans are merely organisms acting according to their nature, and that much of the human experience cannot be quantified as much as science has tried to do so.

Saskia Holmkvist, Blind Understanding, 2009, 12:05

In Audre Lorde’s seminal speech, The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action, she urges the audience to consider their commitment to language and the power of language. It is not only imperative to interrogate the truths we speak, but to examine the language in which these truths are spoken. “What are the words you do not yet have?” Lorde asks, “What do you need to say? What are the tyrannies you swallow day by day and attempt to make your own?”

In Blind Understanding, Holmkvist poses a parallel question: “How do we know what we think we know?” Through a series of loosely connected fragments, the artist meditatively explores the arbitrary codification of language and its relation to power, change, and assimilation. Holmkvist illustrates how our modes of communicating are rarely neutral and at times insufficient, yet perpetually in flux.

==========================

Erika DeFreitas is a Scarborough-based artist whose practice includes the use of performance, photography, video, installation, textiles, works on paper, and writing. Placing an emphasis on process, gesture, the body, documentation, and paranormal phenomena, she works through attempts to understand concepts of loss, post-memory, inheritance, and objecthood.

Johan Grimonprez’s work dances on the borders of practice and theory, art and cinema, documentary and fiction, demanding a double take on the part of the viewer. Informed by an archeology of present-day media, his work seeks out the tension between the intimate and the bigger picture of globalization. It questions our contemporary sublime, one framed by a fear industry that has infected political and social dialogue. By suggesting new narratives through which to tell a story, his work emphasizes a multiplicity of realities.

In Saskia Holmkvist’s work, questions of agency and professionalized language are explored through fractured narrative, employing performance, orality, film and improvisation. The works address consequences of power structures in communication such as translatability of subject positions as well as historical trajectories and post colonial presence by interacting with methods of communication borrowed from fields such as interpretation, psychology, journalism, and improvisational theatre.

================================

PROGRAM #2 Curated by Warren Chan

.exe

What does hope look like in the digital age? As digital depictions of the world become increasingly integral to our experience of the world, to live in a world with hope requires also finding hope in the digital realm. Yet, I sometimes find it difficult to be hopeful in an environment where we have been reduced to data points and our fates seem predetermined by code and algorithms.

The world we live in is a hybrid of the physical space we occupy and the digital spaces through which our vision of the world is continually refracted. As our experiences of reality are subsumed by experiences defined by corporate technologies, liberation from this mediated version of the world appears distant. What hope remains in finding humanity and freedom in a digital reality obfuscated by corporate agendas, where the language of ones and zeroes have been co-opted by corporate tech development?

In this program, I find hope in this digital reality through video works that recontextualize digital images, reject the rules of virtual realities, and interrogate the boundaries between physical space and the infinite worlds on the other side of our screens. Digital photographs, videogame worlds, and computer-generated realities are critically examined in these video works. Through this, I find hope that the opaque systems of the digital world can be understood, reclaimed, and reshaped.

Beginning with the white light of a digital screen and ending with the black void of digital nothingness, the extremes of the digital world are symbolized here. By titling this program .exe, I aim to represent hope in the digital age as executable and actionable. The featured artists here do not find liberation by opting out of new technology. Rather, they confront the new status quo and carve out their own spaces of reflection and expression within this new digital world.

Hope here lies not in Ludditism but in methods of participation that critically engage with these mediums and reject the corporate-defined parameters of these technologies.

Warren Chan is currently completing his MA in Cinema and Media Studies at York University, where he is researching the usage of A.I. generated images in experimental cinema. Outside of his studies, Warren is a filmmaker with an interest in experimental video works that analyze digital and new media technologies.

================================

.exe

Yoshiki Nishimura, Somewhere, 2016, 07:55

In Somewhere, the natural world and the digital world form a dialogue as footage of ocean waves are translated into 3D computer images. These resulting images of waves may not represent any physical location, but this video work argues that these uncanny bodies of water do, in fact, exist somewhere. Nishimura documents and explores digital space as real and meaningful, and foregrounds its relation to natural space. Digital images here are not mechanical reproductions of scenes in the natural world, but acts of creation that use real world references to construct a new space.

In this digital somewhere, we confront the black void of nothingness beyond the horizon. Shrouded in darkness, the image is at first haunting and alien. Yet, as the computer generated sun sets, there is hope that it will rise once again in a new day–a reminder that the future of this digital landscape has not yet been determined.

Peggy Ahwesh, She Puppet, 2001, 15:15

Most virtual worlds of videogames are governed by rules that dictate what one can and cannot do. In She Puppet, Ahwesh uses the Tomb Raider videogame series to examine the limits of our actions in these coded realities and posits that we can reject those rules and find liberation within the parameters of these spaces. Through this defiance of the videogame’s predetermined goals and limitations, the virtual world becomes a space of reflection and expression.

Death in games is intended to be a lose-state. Yet, Ahwesh recontextualizes death here and examines it as a victorious liberation from the confines of the videogame world’s rules. Death symbolizes defiance of the world’s rules and with each death, one is reborn once again to keep forging their own path. Accompanied by quotations from Fernando Pessoa, Joanna Russ, and Sun Ra, Ahwesh turns Tomb Raider’s world into a platform to explore themes of identity and gender.

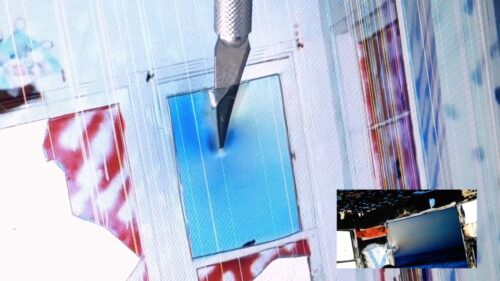

Alejandro Šajgalík, zuma_cuts.mov, 2016, 06:06

Zuma was a photo series by John Divola, wherein the deterioration of an abandoned building used for firefighter training was documented over a year. Contributing to the building’s decay himself during his photography, Divola frames his process of documentation as part of the structure’s continued change.

In zuma_cuts.mov, Šajgalík recontextualizes these images on the computer screen and continues the building’s deterioration as he cuts into the screen with a utility knife. The image on the screen distorts under the blade, foregrounding the materiality of the digital image and its existence within physical space. As the view outside the window is replaced by whiteness, the image ceases to index an absolute space in the physical world, but becomes a window to the infinite space on the other side of the screen. The building Divola photographed lives on in this digital space and continues to change. Through this, Šajgalík investigates the reciprocal relationship of the digital and non-digital.

Friday, October 16, 2020, Chan in conversation with artists Alejandro Šajgalík, Peggy Ahwesh, and Yoshiki Nishimura.

==========================

Alejandro Sajgalik’s work draws from his academic background in architecture and urban sociology, as well as his performance practice. A self-taught interdisciplinary artist, Sajgalik has explored a wide array of artforms including music, dance, video, and text.

Peggy Ahwesh began her career using Super-8 film and has since experimented with a diverse range of mediums, including found footage, digital animation, and Pixelvision video. Her wide breadth of works take on different formats and styles, but are unified by a distinct voice that uses levity to investigate digital culture and gender identity.

Yoshiki Nishimura is an experimental filmmaker who primarily works with 3D computer graphics. Through this, Nishimura examines the relationship between real and virtual worlds. He teaches film and media arts at Tohoku University of Art and Design in Yamagata, Japan.

================================

PROGRAM #1 Curated by Madeline Bogoch

Alternate Arrangements: Subjective Impulses and Social Memory

Outside of this residency I work in a video archive, so much of my day is spent organizing content in a way that is legible to those who wish to access it. Despite my best efforts, the residues of my own subjectivity inevitably leave their mark on this process. In reflecting on this intrusion of the self into the realm of objectivity, I gravitated towards works that develop their own distinctive methods of sorting through the excess of images and content we exist amongst. This program presents three films: The Innocents by Jean-Paul Kelly (2014), Bunte Kuh by Parastoo Anoushahpour, Ryan Ferko, and Faraz Anoushahpour (2015), and Hobbit Love is the Greatest Love by Steve Reinke (2007). Relying heavily on found imagery, these works are evidence of what Hal Foster refers to as the “archival impulse,” a utopian drive which seeks to gauge the present and forecast the future through the remnants of the past.

There is an economical quality in this impulse of recombination and juxtaposition, one which produces meanings greater than the sum of their parts. In The Innocents, this is used to undermine the fidelity of the documentary genre, while Bunte Kuh obscures the prototypical travelogue into something hazier and more ominous. This impulse reappears in Reinke’s acerbic video essay Hobbit Love is the Greatest Love, most explicitly in the image stream of U.S. military personnel killed in the Second Gulf War, arranged by attractiveness. While the relation between Kelly’s images remain opaque, his and Reinke’s image streams share a libidinal classification system which signals the desire to parse an overwhelming supply of content through a personal logic. Something in this drive speaks to an empathic sensibility shared by all three works, which pursues new dialogues by superimposing the artist’s own inflections onto their sources. By developing new ways of ordering and thinking about existing material, these artists exhibit a private approach to the public archive. I present these works as ways of overcoming an impasse of imagination, clever approaches that incubate new futures through existing material and unlikely interlocutors.

Madeline Bogoch is a writer and MA student in the art history department at Concordia University. Her work is focused primarily on experimental moving image practices, specifically: circulation and dispersion, media preservation, and the aesthetics of obsolescence. In addition to her academic work she is a member of the programming committee for the Winnipeg Underground Film Festival (WUFF) and is a Project Coordinator at Video Pool Media Arts Centre in Winnipeg, Manitoba.

================================

Steve Reinke, Hobbit Love is the Greatest Love, 2007, 14:00

Reinke opens his desktop essay with an immodest proposal to update Adrian Piper’s Calling Card project. Penned as an open letter, and speaking in the plural pronoun “we,” Reinke offers a sarcastic polemic against “that increasingly impossible category: autobiography.” In a later chapter, Reinke graphically elaborates his hyperbolic historical diagram as a diamond shape, the widest point at the centre representing the present situated between two points, past (“trauma”) and future (“apocalypse”). He arrives at this figure by combining a teleological view of history hurtling towards eventual apocalypse, with a retrospective view of biography which is derived out of an unnamed proto-trauma. Reinke’s work thrives at this crossroad of biography and history. There’s an elegant brevity to his organizational logic, often illustrated through diagrams and delivered by his resonant voice and authoritative tone. In the final chapter of Hobbit Love, Reinke presents a series of portraits of military casualties from the Second Gulf War, arranged by attractiveness. While the conceit of this gesture is certainly provocative, the sheer volume of the sample size reflects the unmanageable violence with which we are continually confronted. In response to this magnitude Reinke responds rationally, exhibiting them according to his own desire—a way of ordering the world and its overabundance of images and trauma, which makes about as much (non)sense as anything else.

Faraz Anoushahpour, Parastoo Anoushahpour, Ryan Ferko, Bunte Kuh, 2015, 5:45

Tolstoy wrote that that all happy families are alike. Following from that, it could be said that all travel photos share a similar homogeneity. In Bunte Kuh, the artists mix documentation of a family trip with footage of swimming koi fish. The image rapidly flickers between the two, with overlaid audio of fireworks, and a voice-over reading a found postcard. The integration of the layered audio against the sharp edits creates a rhythmic cadence, which lulls you into a trance-like reverie. The tone and the content strikes a stark contrast—an implication of violence lurking behind the leisure-class luxury of seeking exotic experiences. This disorienting ambience is produced by the artists’ manipulation of the audiovisual afterlife of memories, defamiliarizing their otherwise prosaic content. What transpires is a sensation not unlike déjà vu, an elusive familiarity, which leaves an eerie residue in its wake.

Jean-Paul Kelly, The Innocents, 2014, 12:50

The Innocents begins with the artist presenting 42 prints of images culled from online sources. Lacking any explicit criteria, the stream includes images of violence, sex, and several portraits of Truman Capote, a figure who functions as a sort of conceptual guide throughout the film. Each photo has one or more holes punched out, voids which reappear later as solids in a Super 8 animation. Between these scenes, Capote reappears through a surrogate who wears a plastic bag over his head, and re-enacts an interview with the author, mimicking his gestures. What Capote refers to in the interview as “poetic reporting” could be aptly applied to Kelly’s practice as a whole, particularly his capacity to extract the essence of the documentary image by prying it apart at the seams. In The Innocents, the source material is reduced to its most basic properties, only to be reassembled in new forms which probe at the tangled connections between material, representation, and perception.

Friday, September 25, 2020, Bogoch in conversation with artists Jean Paul Kelly, Parastoo Anoushapour, Faraz Anoushapour, and Ryan Ferko, and Steve Reinke.

================================

Jean-Paul Kelly is a Toronto-based artist working in video, drawing, and photography. His practice questions the limits of representation by examining complex associations between found photographs, videos, sounds, and online media streams. He has extensively exhibited and screened works across North America and Europe and is currently a Visual Studies lecturer at the University of Toronto.

Parastoo Anoushahpour, Faraz Anoushahpour, and Ryan Ferko have worked in collaboration since 2013. Using various performative structures, their projects explore collaboration as a way to upset the authority of a singular narrator or position. Recent work has been shown at New York Film Festival, TIFF , Gallery 44 and Trinity Square Video in Toronto.

Steve Reinke is a Canadian artist and writer best known for his diaristic videos which express his desires and pop culture appraisals with endearing wit. His work is screened widely, and is in several collections, including the Museum of Modern Art (New York), the Pompidou (Paris), and the National Gallery (Ottawa).